Review of Text-to-Voice Synthesis Technologies

16 minute read

Eugene Wang, fa20-523-350, Edit

Abstract

The paper is about the most popular and most successful voice synthesis methods in the recent 5 years. Area of examples that would be explored in order to produce such a review paper would consist of both academic research papers and examples real world successful applications. For each specific example examined, its dataset, theory/model, training algorithms, and the purpose and use for that specific method/technology would be examined and reviewed. Overall, the paper will compare the similarities and differences between these methods and explore how big data enabled these new voice-synthesis technologies. And last, the changes these technologies will bring to our world in the future is discussed and both positive and negatives implications are explored in depth. This paper is meant to be informative to the both general audience and professionals about the how voice-synthesizing techniques has been transformed by big data, most important developments in the academic research of this field, and how these technologies are adopted to create innovation and value. But also to explain the logic and other technicalities behind these algorithms created by academia and applied to real world purposes. Codes and datasets of voices will be supplemented as for the purpose of demonstrations of these technologies in working.

Contents

Keywords: Text-to-Speech Synthesis, Speech Synthesis, Artificial Voice

1. Introduction

The idea of making machines talk has be around for many over 200 years. For example, in as early as 1779, a scientist called Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein built models of the human vocal tract (the cavity in human beings where voice is produced in) that can produce the sound of long vowels (a, e, i , o, u)1. From then till the 1950s, there have been many successful studies and attempts to make physical models that mechanically imitate the human voice. In the late 1960s, the people trying to synthesize human voice started to do it electronically. In 1961, by utilizing the IBM 704 (one of the first mass produced computers), John Larry Kelly Jr and Louis Gerstman, made a voice recorder synthesizer (aka. vocoder). Their system was able to recreate the song "Daisy Bell"2. Before the current deep neural network trend, modern systems for text-to-Speech (TTS) or speech synthesis has been dominated by concatenative methods and then statistical parametric methods. Creating the ability for humans to converse with computers or any machines is a one of those age-old dreams of humans. A human-computer interaction technology that provides the computers to comprehend raw human speech has been revolutionized in last couple of years by the amount of big data we have now and the implementation, mainly deep neural networks, that feeds on big data.

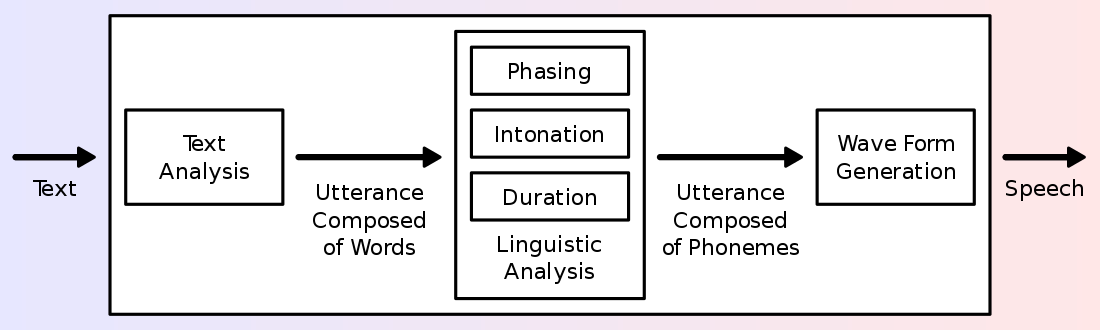

Figure 1: Illustration of a typical TTS system

2. Overview of the Technology

Concatenative methods work by stringing together segments of prerecorded speech segments. The best of concatenative methods is the Unit Selection. The recorded voice segments in unit selection is categorized into individual phones, diphones, half-phones, morphemes, syllable, words, and phrases. Unit selection divides a sentence into segmented units by a speech recognizer, then these units are filled in with recorded voice segments based on parameters like frequency, duration, syllable position, as well as these parameters of its neighboring units 3. The output of this system can be undistinguishable from natural voice, but only in very specific context that it is being tuned for and provided that the system has a very large database of speeches, usually in the range of dozens of hours of speech. This system suffers from boundary artifacts, which are unnatural connections between the sewed-together speech segments.

What came after concatenative methods are the statistical parametric methods, it solved many of the concatenative method’s boundary artifact problems. Statistical Parametric methods are also called Hidden-Markov-Models-based (HHM-based) methods, because HMM are often the choice to model the probability distribution of speech parameters. The HH model selects the most likely speech parameters like frequency spectrum, fundamental frequency, and duration (prosody), given the word sequence and trained model parameters. Last, these speech parameters are combined to construct a final speech wave form. Statistical parametric synthesis can be described as /“generating the average of some sets of similarly sounding speech segment” 4. The advantage that statistical parametric methods have over concatenative methods is the ability to modify aspects of the speech such as the gender of speaker, or the emotion and emphasis of the speech. The use of statistical parametric methods marks the beginning of the transition from a knowledge-based system to a data-based system for speech synthesis.

From a high-level point of view, a text-to-speech system is composed of two components. The first component starts with text normalization, also called preprocessing or tokenization. Text normalization converts symbols, numbers, and abbreviations into normal dictionary words. After text normalization, the first components end with text-to-phenome. Text-to-phenome is the process of dividing the text into units like words, phrases, and sentences; then converting these units into target phonetic representations, or target prosody (frequency contour, durations, etc.) The second component, often called the synthesizer or vocoder, takes the symbolic phonetic representations and converts them into the final sound.

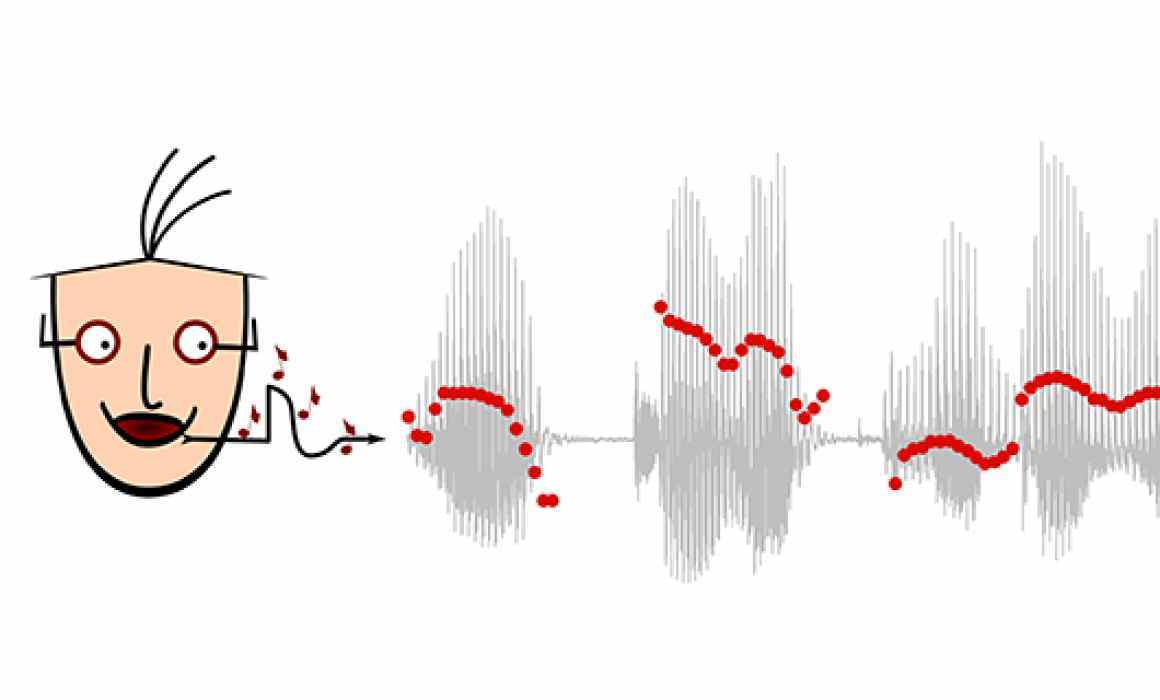

Figure 2: Illustration of prosody

3. Main Example: Tacotron 1 & 2 and WaveNet for Voice Synthesis

The Tacotron a TTS system that begin by using a sequence to sequence architecture implemented with neural network to produce magnitude spectrograms with a given string of text. The first component of Tacotron is one single neural network that was trained from 24.6 hours of speech audio recorded by a professional female speaker. The effectiveness of a neural network in speech synthesis shows how big data approaches are improving and changing up the speech synthesis methodologies. Tacotron uses the Giffin-Lim algorithm for its second component, the vocoder. The authors note that their choice of approach for the second component is only used as a placeholder at that time, and they anticipated that the Tacotron is be more advanced with alternative approaches for the second component, the vocoder, in the future 5. And Tacotron 2 is what the authors of the original Tacotron might have envisioned.

Tacotron 2 is a TTS system built entirely using neural network architectures for both its first and second component. Tacotron 2 combines the original tacotron’s first component and combine it with Google’s WaveNet that serves as the second component. The tacotron-style first component responsible for preprocessing and text-to-phenome, produces mel spectrograms given the original text input. Mel spectrograms are representations of frequencies in mel scale as it varies over different time. The mel spectrograms are then fed into WaveNet, a vocoder that serves as the second component, which outputs the final sound 6.

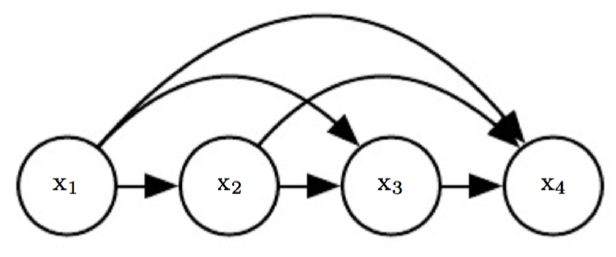

WaveNet is a deep neural network model that can generate raw audio. What is different about WaveNet is that it can model and generate the raw audio form. Typically, audio is digitized by sampling a single data point for every very small-time interval. A raw audio wave form typically contains 16,000 sample point in every second of audio. With that many sample points per second, an audio clip of a simple speech would contain millions and billions of data points. To make a generative model for these sample audio points, the model needs to be autoregressive, meaning every sample point generated by the model is influenced by its earlier sample points that is also generated by the model itself 7. A very difficult challenge that DeepMind solved. Before DeepMind came up with WaveNet, they made pixelRNN and pixel CNN. Which proved that it is possible to generate a complicated image one pixel at a time given a large amount of quality training data. This time instead of an image generated a pixel at a time, an audio clip is generated one sample point at a time.

WaveNet is trained with audio recordings, or wave forms, from real human speech. After training the model, WaveNet can generate synthetic utterances of human speech that does not actually mean anything. WaveNet would be fed a random audio sample point, and it will predict the next audio sample point and feed it back to itself and generating the next one, so on and so forth, producing complex realistic speech wave form. To apply WaveNet to TTS systems, it would have to be trained not only the human speech but also each training sample’s corresponding linguistic and phonetic features. This way, WaveNet would be conditioned on both the previous audio sample points and the words we want WaveNet to say. In a real working TTS system, these linguistic and phonetic features are the product of the first component, which is responsible for text-to-phenome 7.

Figure 3: Illustration of an Autoregressive Model

3.1 Application and Implications of a lifelike TTS system like Tacotron 2

The powerful and lifelike TTS system by Tacotron 2 and Wavenet enhances many real-life applications that relies on having a machine talk, but most predominantly in human-computer interaction like smart phone voice assistant. And naturally, with a TTS system so lifelike, there are some concerns it would be used for nefarious purposes; but it also enables great enhancements to current applications of TTS systems. In one example researchers are able to build system that adds a speech encoder system on top of Tacotron 2 and Wavenet, and make it so it would be able to clone anyone’s voice signature and produce any speech wave forms with that person’s voice with just a few seconds of his or her original speech recording 8. The objective of the speaker encoder network added on to Tacotron 2 and Wavenet is to learn a high quality representation of a target speaker’s voice. In other words, the speaker encoder network is made to learn the “essence” and intricacies of human voices. The theory is that with this speech embeddings (representations) of a particular voice signature, Tacotron 2 and Wavenet would be able to use that to generate brand new speeches with the same voice signature. The most importance reason why this system is able to work with and extrapolate from an unseen and small amount of audio recording of the target speaker is a large and diverse amount of data of different speakers used to train the speaker encoder network 8. This demonstrates that not only big data contributed to the success of this network but that the big data also has to be the right data, with “right” being having a diverse amount of different variations in speakers.

One possible benefit of such a system can provide is in speech to speech translation across different languages. Because the system only requires couple seconds of un-transcribed reference audio recorded from the target speaker, this system can be used to enhance current, top of the line, speech to speech translation system like Google Translate by generating the output speech that is in another language with the original speaker’s voice. This makes the generated speech more natural and realistic sounding for the intended listener of the translated speech in a real world setting 8. An example of a fun implementation of such a system is the option to choose celebrity’s voices, like John Legend’s voice, as the voice of your Google Assistant in your smart phone or your Google Home 9. But a different and potentially dangerous implication of a system being misused and abused is not hard to imagine as well, especially that sometimes the artificially synthesized speech by these latest TTS systems are rated as indistinguishable from real human speech 7. According to a study, our brain does not register significant differences between a morphed voice and a real voice 10. In other words, while we can still somewhat distinguish between a genuine and artificial voice, we probably will be fooled most of the time if we are not particularly paying attention and on the look out for it. For example, people can be fooled into believing or doing certain things, because the voice that they talked too belongs to someone who that trust or someone who they believe holds a certain type of authority. While there are people coming up with technical solutions to safeguard us, the first step is to raise awareness about the existence of this technology and how sophisticated it can be 9.

4. Other Example A: Deep Voice: Baidu’s Real Time Neural Text-to-Speech System

Just like Google’s Tacotron and Wavenet, this paper’s authors from Baidu, a Google competitor, also elected to use neural networks and big data to train and implement every component of a TTS system, called Deep Voice. This further demonstrates the effectiveness of the approach of using big data to train deep neural networks. Baidu’s Deep Voice TTS system is consisted of five components, in their respective order they are: grapheme-to-phoneme model, segmentation model, phoneme duration model, fundamental frequency model, and audio synthesis model. The first grapheme-to-phoneme model is self explanatory, it is referred to as the “first component” of a TTS system in a two-component view. Grapheme-to-phoneme model converts text into phonemes. The second segmentation model is used to draw the boundaries between each phoneme (or each utterance) in the audio file given the audio file’s transcription. The third phoneme duration model predicts the time or duration of each phoneme. The forth fundamental frequency model predicts whether or not each phoneme is “silent”, as sometimes a part of a word is spelled but not voiced; if it is voiced, the model predicts its fundamental frequency. The fifth and final model, the audio synthesis model, combines the output of the prior four models and synthesize the final finished output audio. Baidu’s audio synthesis model is a modified version of DeepMind’s WaveNet 11.

All five models that compose Baidu’s Deep Voice are implemented with neural networks, making Deep Voice also an truly end to end “neural speech” synthesis model, also serving as a proof that the deep learning with big data approaches can be applied to every part and component of a TTS system. As to making it real time, the TTS system needs to be optimized to near instantaneous speeds. Baidu’s researchers experimented with various hyperparameter configurations, also including changing the amount of detail (and size) of the training data, data type, size/type of computational medium (CPU, GPU), amount of nonlinearities in the model, different memory cache techniques, and the overall size (computational requirements) of the models. They timed each of these configurations and scored the quality (MOS, Mean Opinion Scores) of each of their synthesized speech. The result shows a trade off between speech quality and synthesis speed. Without sacrificing too much audio quality, Deep Voice is able to produce a sufficient quality, 16 kHz audio, at 400 time faster that WaveNet and achieving the goal of making Deep Voice real-time or faster than real-time 11.

5. Other Example B: Siri’s Hybrid Mixture Density Network Based Approach to TTS

Siri is Apple’s virtual assistant that is communicated through the use of natural language user interface, predominantly through speech. Siri is capable of perform user instructed actions, make recommendations, and more by delegating requests to other internet services. Apple’s three operating systems: iOS, iPadOS, watchOS, tvOS, and macOS all come with Siri. Siri was first released with iOS in iPhones in 2011, after Apple acquired it a year before. Within the components that make up Siri is a TTS system that is used to generate a spoken, verbal response to user’s input. Throughout the years, different techniques and technologies have been used to implement the TTS system of Siri in order to make it better.

The old Siri uses predominantly a unit selection approach to its TTS system. Within predictable and narrow usage applications, older unit selection speech synthesis method still shines, because it can still produce adequately good speeches given that the system contains a very large amount of quality speech recordings. But the out performance of deep learning approaches over traditional methods had become more and more clear. Apple gave Siri a new and more natural voice by switching their old TTS system to one implement with a hybrid mixture density network based unit selection TTS system 12.

This hybrid mixture density network based unit selection approach first uses a function to pick the most probable audio units for each speech segments, then uses a second function to find the most optimal (natural sounding) combination of the selected candidates for each broken down segment of the entire speech. The role of the mixture density network here in Siri is to serve as these two functions mentioned: a unified target model and concatenation model that is able to predict distributions of the target features of a speech and the cost of concatenation between the sample audio units. The function that models the distributions of target features used to be commonly implemented with hidden Markov models in a statistical parametric approaches of TTS. But it has since been replaced by the better deep learning approaches. The concatenation cost function is used to measure the acoustic difference between two units for the purpose of guaging their sound’s naturalness when concatenated. Hence the concatenation cost function is what is used during the search for the optimal sequence (or combinations) of units in the unit audio speech space 12.

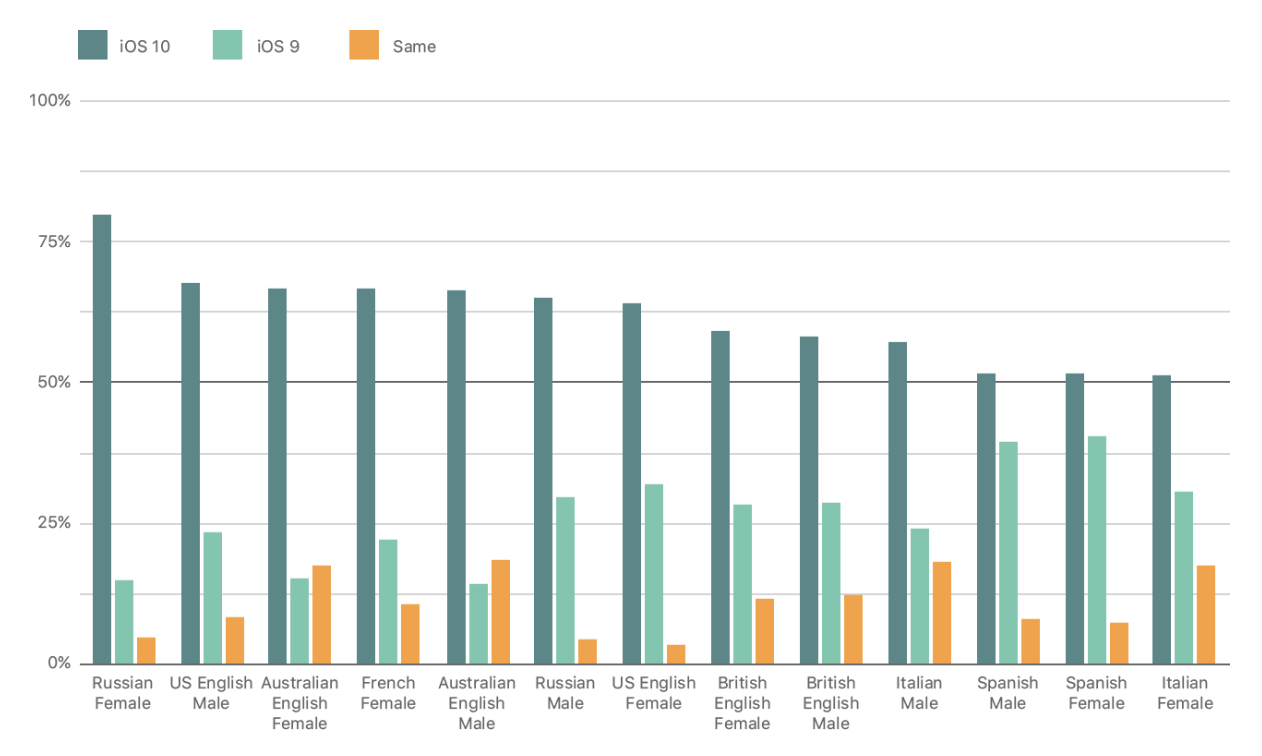

Starting in iOS 10 in 2017 until this moment, Siri’s TTS system had been upgraded with neural network approaches, and the new Siri’s voice is demonstrated to be massively preferred over the old one in controlled A/B testing 12.

Figure 4: Results of AB Pairwise Testing of Old and New Voices of Siri

6. Conclusion

The Tacotron, Deep Voice, and Siri’s TTS system are the three advance cutting edge TTS technologies. All of them are designed with deep neural networks as the main work horse with big data simultaneously acting as their food and their vitamins. With the knowledge of the history of TTS systems and its how its basic theoretical components, and through these three examples, we can see how big data and neural networks have revolutionized the speech synthesis technology field. Although, these advancements open potential dangers of it being used to exploit trust between people by the means of impersonation, they do provide us with even more real life benefits ranging from language translation to personal virtual assistants.

7. References

-

J. Ohala, “Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein: Pioneer in Speech Synthesis”, ICPhS. (2011) https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/icphs-proceedings/ICPhS2011/OnlineProceedings/SpecialSession/Session7/Ohala/Ohala.pdf ↩︎

-

J. Mullennix and S. Stern, “Synthesized Speech Technologies: Tools for Aiding Impairment”, University of Pittsburh at Johnsonstown (2010) https://books.google.com/books?id=ZISTvI4vVPsC&pg=PA11&lpg=PA11&dq=bell+labs+Carol+Lockbaum&hl=en#v=onepage&q=bell%20labs%20Carol%20Lockbaum&f=false ↩︎

-

A. Hunt and A. W. Black, “Unit Selection in a Concatenative Speech Synthesis System Using a Large Speech Database”, ATR Interpreting Telecommunications Research Labs. (1996) https://www.ee.columbia.edu/~dpwe/e6820/papers/HuntB96-speechsynth.pdf ↩︎

-

A. W. Black, H. Zen and K. Tokuda, “Statistical Parametric Speech Synthesis”, Language Technologies Institute, Carnegie Mellon University (2009) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2009.04.004 ↩︎

-

Wang, Yuxuan, et al. “Tacotron: Towards End-to-End Speech Synthesis”, Google Inc, (2017) https://arxiv.org/pdf/1703.10135.pdf ↩︎

-

Shen, Jonathan, et al. “Natural TTS Synthesis by Conditioning WaveNet on Mel Spectrogram Predictions”, Google Inc, (2018) https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05884.pdf ↩︎

-

Oord, Aaron van den, et al. “WaveNet: a Generative Model for Raw Audio”, Deepmind (2016) https://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.03499.pdf ↩︎

-

Jia, Ye et al. “Transfer Learning from Speaker Verification to Multispeaker Text-To-Speech Synthesis”, Google Inc., (2019) https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.04558 ↩︎

-

Marr, Bernard, “Artificial Intelligence Can Now Copy Your Voice: What Does That Mean For Humans?”, Forbes, (2019) https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2019/05/06/artificial-intelligence-can-now-copy-your-voice-what-does-that-mean-for-humans/ ↩︎

-

Neupane, Ajaya, et al. “The Crux of Voice (In)Security: A Brain Study of Speaker Legitimacy Detection”, NDSS Symposium, (2019) https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ndss2019_08-3_Neupane_paper.pdf ↩︎

-

O. A. Sercan, et al. “Deep Voice: Real-time Neural Text-to-Speech”, Baidu Silicon Valley Artificial Intelligence Lab, (2017) https://arxiv.org/abs/1702.07825 ↩︎

-

Siri Team, “Deep Learning for Siri’s Voice: On-device Deep Mixture Density Networks for Hybrid Unit Selection Synthesis”, Apple Inc, (2017) https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/siri-voices ↩︎