Review of the Use of Wearables in Personalized Medicine

10 minute read

Adam Martin, fa20-523-302, Edit

Abstract

Wearable devices offer an abundant source of data on wearer activity and health metrics. Smartphones and smartwatches have become increasingly ubiquitous, and provide high-quality motion sensor data. This research attempts to classify movement types, including running, walking, sitting, standing, and going up and down stairs, to establish the practicality of sharing this raw data with healthcare workers. It also addresses the existing research regarding the use of wearable data in clinical settings and discusses shortcomings in making this data available.

Contents

Keywords: Wearables, Classification, Descriptive Analysis, Healthcare, Movement Tracking, Precision Health, LSTM

1. Introduction

Wearables have been on the market for years now, gradually improving and providing increasingly insightful data on user health metrics. Most wearables contain an array of sensors allowing the user to track aspects of their physical health. This includes heart rate, motion, calories burned, and some devices now support ECG and BMI measurements. This vast trove of data is valuable to consumers, as it allows for the measurement and gamification of key health metrics. But can this data also be useful for health professionals in determining a patient’s activity levels and tracing important events in their health history?

2. Background Research and Previous Work

Previous work exists on the use of sensors and wearables in assisted living environments. Consumer wearables are commonplace and have been used primarily for tracking individual activity metrics. This research attempts to establish the efficacy of these devices in providing useful data for user activity, and how this information could be useful for healthcare workers. This paper examines the roadblocks in making this information available to healthcare professionals and examines what wearable information is currently being used in healthcare.

2.1 Existing Devices

Existing research focuses on a wide variety of inputs 12. Sensors including electrodes, chemical probes, microphones, optical detectors, and blood glucose sensors are referenced as devices used for gathering healthcare information. This research will focus on data that can be gathered with a modern smartphone or smartwatch. Most of the sensors described are not as ubiquitous as consumer items like FitBits or Apple Watches. Furthermore, many users report diminished enthusiasm towards wearables due to complex sensors and pairing processes 3. Focusing on devices that are already successful in the consumer market ensures that the impact of this study will not be confined to specific users and use cases. Apple has released a suite of tools for interfacing with device sensors, and recently launched ResearchKit and CareKit, providing a framework for researchers and healthcare workers to collect and analyze user data 2. There are several apps available that utilize these tools, including Johns Hopkins' CorrieHealth app, which helps users manage their heart health care and shares data with their doctors. This is an encouraging step towards streamlining the sharing of wearable data between patients and healthcare professionals, as Apple provides standards for privacy, consent, and data quality.

2.2 Need for Wearable Data in Healthcare

Previous studies have indicated the significance of precision health and the need for patient-specific data from wearables to be integrated into a patient’s care strategy 4. Wearable data outlining a patient’s sleep, motion habits, heart rate, and other metrics can be invaluable in diagnosing or predicting conditions. Increased sedentary activity could indicate depression, and could predict future heart problems. A patient’s health could be graphed and historical trends could be useful in determining factors that contribute to the patient’s condition. It is often asserted that a person’s environmental factors are better predictors for their health than their genetic makeup 4. Linking behavioral and social determinants with biomedical data would allow professionals to better target certain conditions.

3. Choice of Dataset

The dataset used for this project contains labeled movement data from wearable devices. The goal is to establish the potential for wearable devices to provide high-quality data to users and healthcare professionals.

A dataset gathered from 24 individuals with Apple devices measuring attitude, gravity, and acceleration was used to determine user states. The dataset is labeled with six states (walking downstairs, walking upstairs, sitting, standing, walking and jogging) and each sensor has several attributes describing its motion. The attitude, gravity, and acceleration readings each have three components corresponding to each axis of freedom. Many smartphones and wearables already offer comprehensive sleep tracking features, so sleep motion data will not be considered for this study. The CrowdSense iOS application was used to record user movements. Each sensor was configured to sample at 50hz, and each user was instructed to start the recording, and begin their assigned activity.

4. Methodology and Code

The IPython notebook used for this analysis is available on the GitHub repository.

The analysis of relevant wearable data is undertaken to determine the accuracy of activity information. This analysis will consist of a brief descriptive analysis of the motion tracking data, and will proceed with attempts to classify the labeled data.

First, the data has to be downloaded from the MotionSense project on GitHub. A basic descriptive analysis will be performed, visualizing the sensor values for each movement class over time. During the data acquisition, the sensors are sampled at a 50hz rate. Since the dataset is a timeseries, classification methods that take advantage of historical datapoints will be the most effective. The Keras Long Short Term Memory classifier implementation is used for this task. The dataset is first split into its various classes of motion using the one-hot-encoded matrix to filter out each class. Each class is then subdivided into one-second ‘windows’, each with 50 entries. Each window is offset by 10 entries from the previous window. The use of windows allows the model to remain small in size, while still gathering enough information to make accurate classifications. The hyperparameters that can be tuned include:

- Window size (50)

- Window offset (10)

- LSTM size (50)

- Dense layer size (50)

- Batch size (64)

- Epochs (15)

- Dropout ratio (0.5)

The resulting data structure is a 3-dimensional array of shape (107434, 12, 50) for the training set and (32439, 12, 50) for the testing set. The dimensions correspond to the number of windows, the number of movement features, and the number of samples per window, respectively. These windows are then paired with their corresponding movement classifications and fed into a Keras LSTM workflow. This workflow is executed on a standard (non-gpu) Google Colab instance and benchmarked. The workflow consists of the following:

- A Long Short Term Memory layer with the cell count matching the size of the input window (50)

- A Dropout layer to minimize overfitting

- A fully connected layer with relu activation to help learn the weights of the LSTM output

- A fully connected output layer with a softmax activation to return the final classifications

The model is trained in 15 epochs, and uses a batch size of 64 for each backpropagation.

If a classification strategy of sufficient accuracy is possible, it will be determined that wearable data can potentially serve as a useful supplementary source of information to aid in establishing a patient’s medical history.

Reviewing relevant literature is important to determine the current state of wearables research regarding usefulness to healthcare workers and user well-being. Much of this research will be focused on determining the state of wearables in the healthcare industry and determining if there is a need for streamlined data transfer to healthcare professionals.

5. Discussion

The dataset is comprised of six discrete classes of movement. There are 12 parameters describing the readouts of the sensors over time.

5.1 Descriptive Analysis

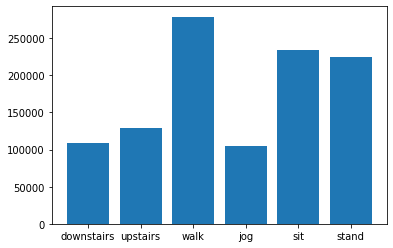

There is an imbalance in the number of datapoints for each class, which could lead to classification errors.

Figure 1: Data distribution per movement class.

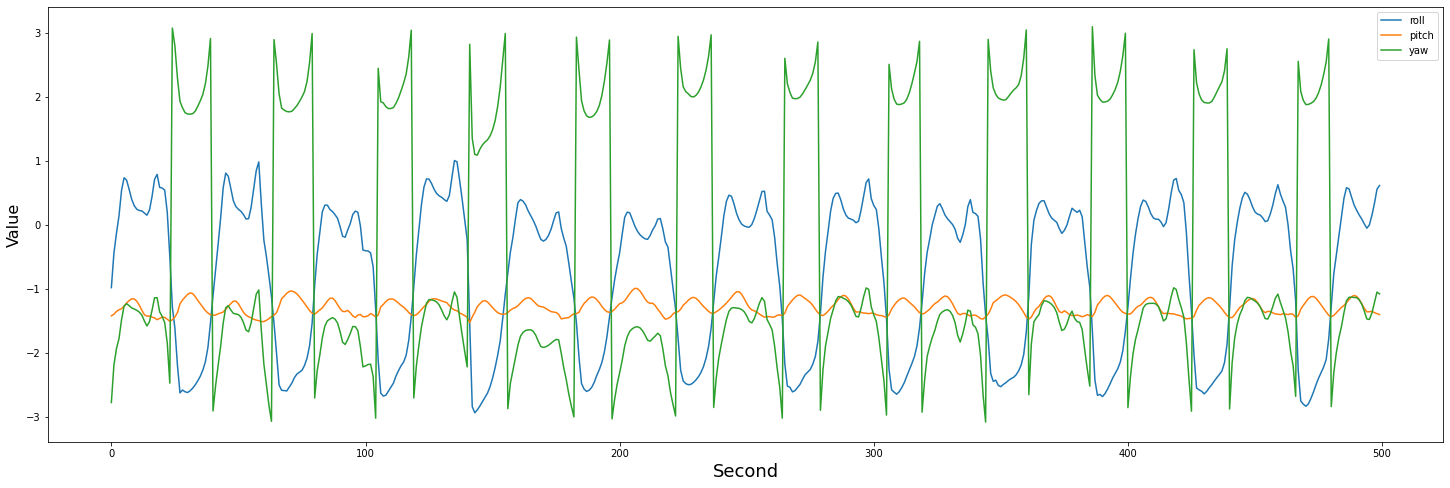

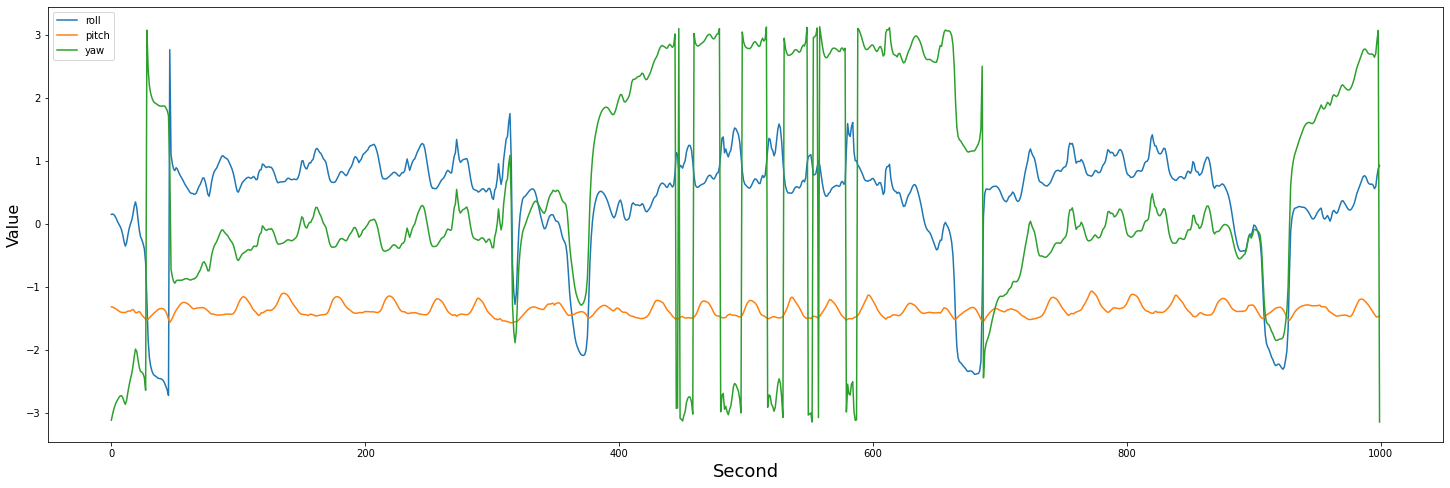

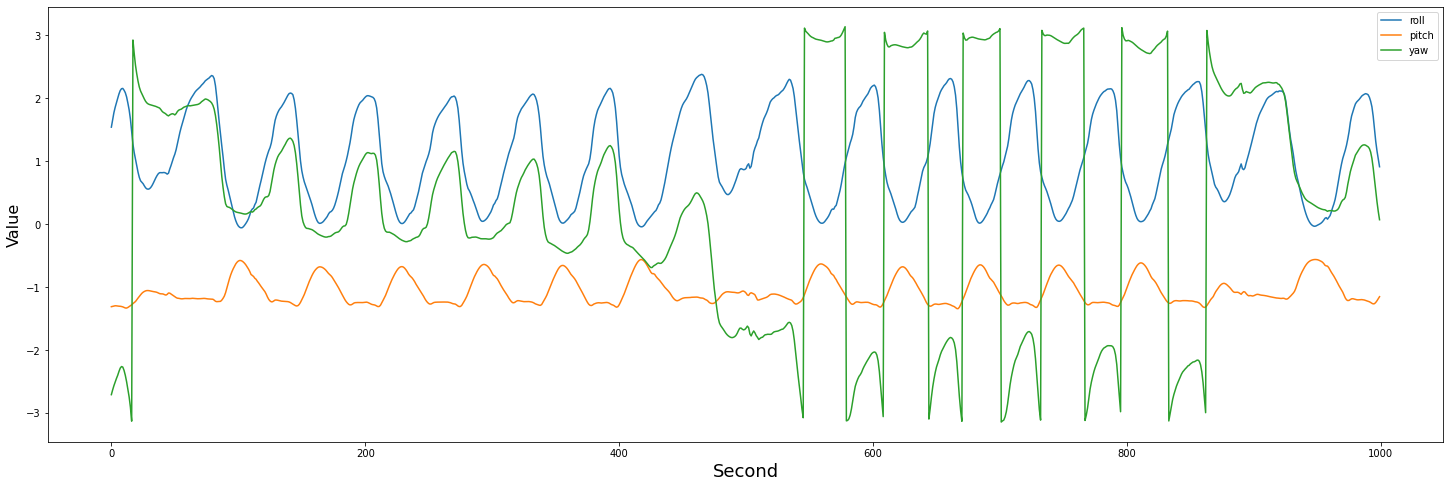

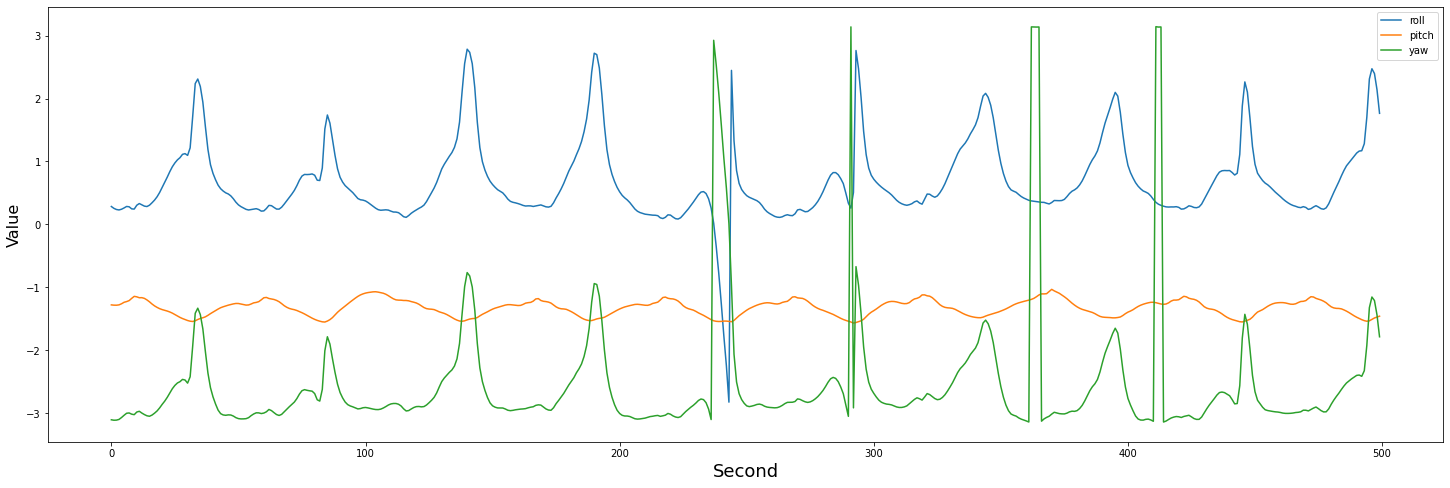

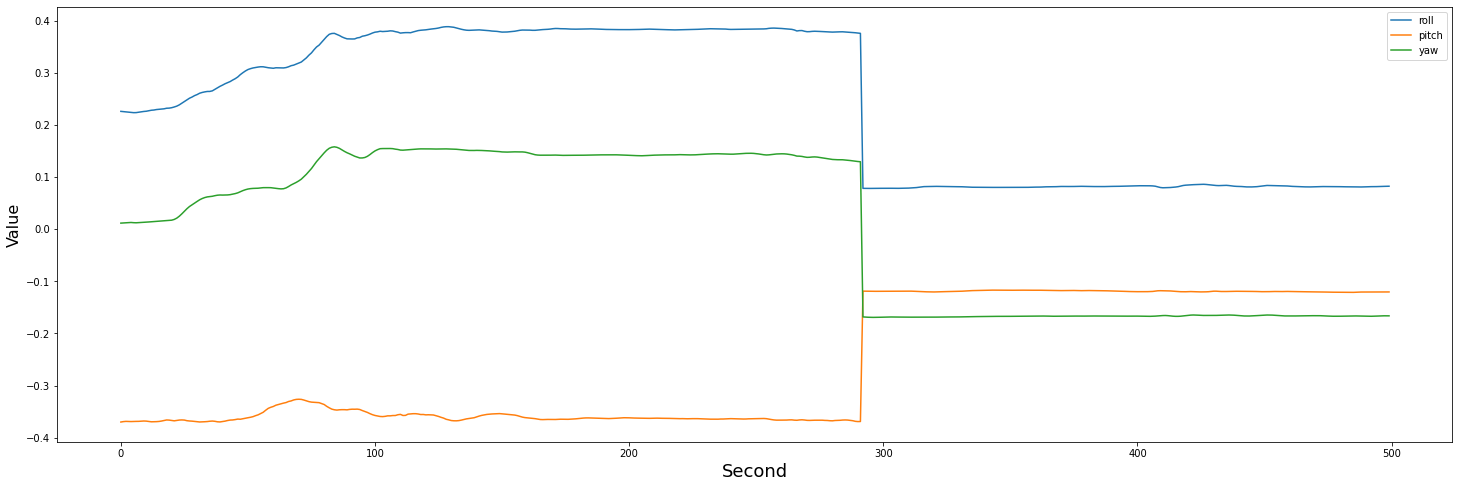

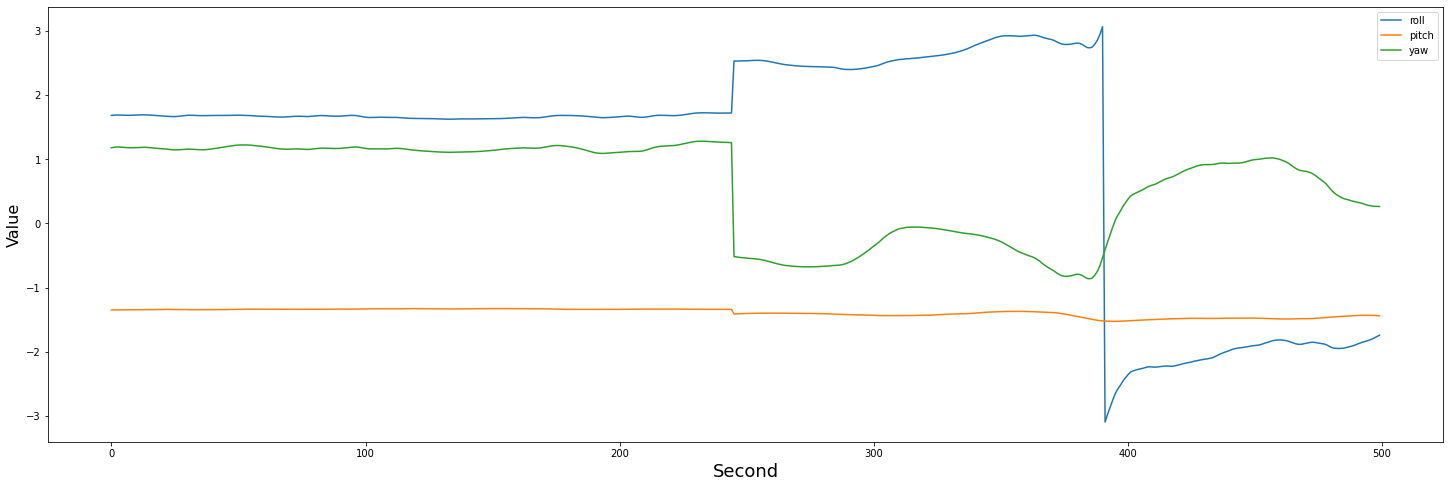

Only roll, pitch, and yaw are shown for clarity and to illustrate the quality of the readings obtained by the sensors. Figures 2-7 illustrate sensor readouts over time for each class of movement.

Figure 2: 10 second sensor readout of a jogging male.

Figure 3: 20 second sensor readout of a female going downstairs.

Figure 4: 20 second sensor readout of a male going upstairs.

Figure 5: 10 second sensor readout of a female walking.

Figure 6: 10 second sensor readout of a male sitting.

Figure 7: 10 second sensor readout of a female standing.

Interestingly, initial classification attempts involving random forests and knn methods performed fairly well despite their inherent lack of awareness of historical data.

5.2 Results

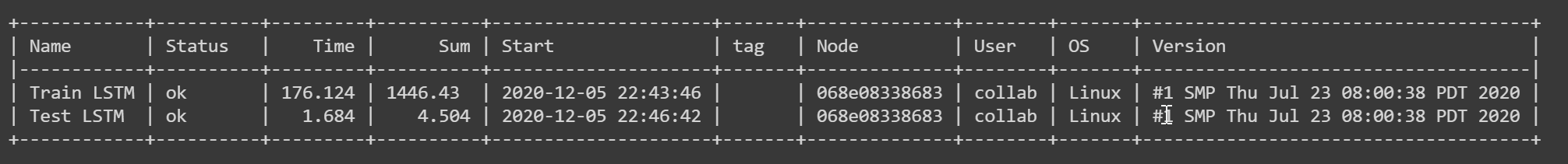

Figure 8: Cloudmesh benchmark for LSTM train and test.

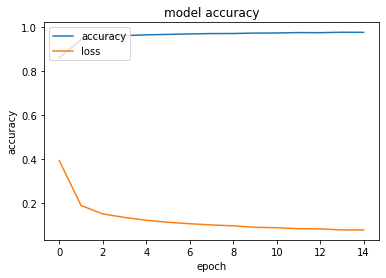

Figure 9 LSTM training and loss curves.

The final accuracy measurement for the LSTM was %95.42. This proves that discrete movement classes can be determined through the analysis of basic sensor data regarding device movement.

6. Conclusion

6.1 Results

Using relatively basic machine learning methods, it is possible to determine with a high level of accuracy the type of movement being performed at a given moment. Viewing the benchmarks, the inference time is rapid, taking only 3 seconds to validate results for the entire testing dataset. This model could be distilled for a production environment, and the rapid inference speed would allow for faster analyses for end users.

6.2 Limitations

The classes of movement considered for this study were limited. For more precise movements, or movement combinations, more data and a more complex model would be required. For example; classifying the type of activity being done while a user is seated, if they are typing or eating. Future research could involve a wider review of timeseries classifiers, including transformers convolutional neural networks, and recurrent neural networks, in order to establish what classification strategy would be best suited for this data. Privacy is also important to consider; raw sensor data could provide malicious actors with information regarding a users daily habits, their gender, their location, and other sensitive data.

Existing research highlights some of the issues with the adoption of wearable devices in healthcare. Inconsistent reporting, usage, and data quality are the most common concerns 25. Addressing these issues through an analysis of data quality and device usage could contribute towards the robustness of this study.

6.3 Impact

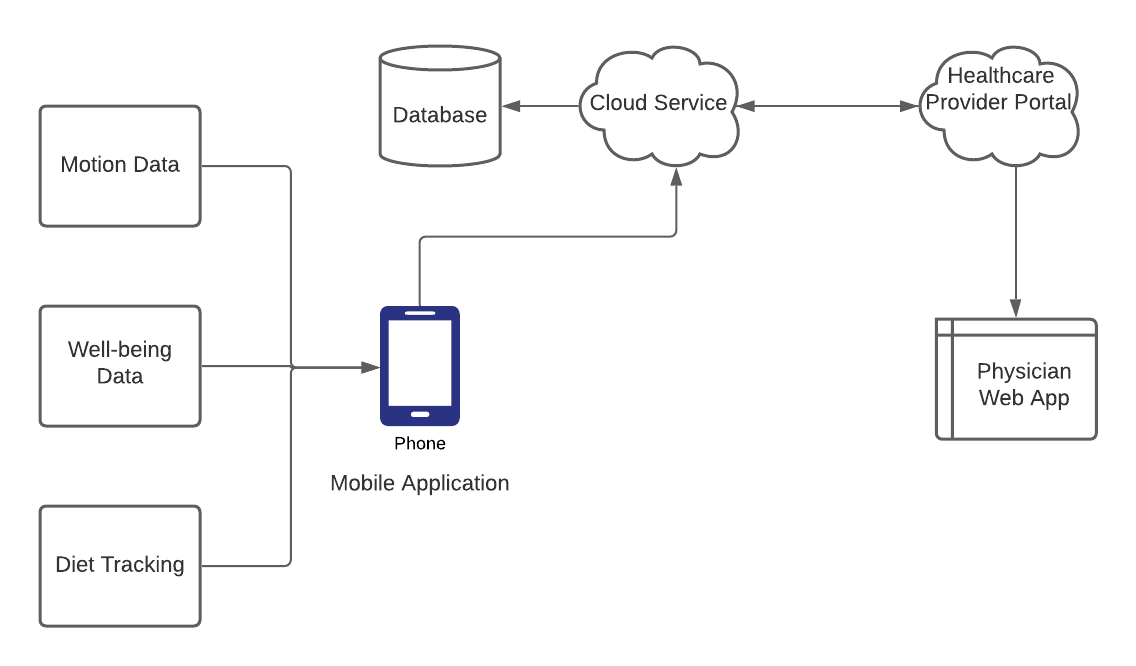

Figure 10 Proposal for integration of wearables data with other data sources and healthcare portals.

Frameworks like Apple CareKit and Google Fit are emerging to address the increasing demand for health tracking applications. There is a need for a more effective pipeline for sharing this information securely with doctors and researchers, and these frameworks are a step in the right direction. Furthermore, this research can be applied towards finding correlations between a patient’s condition and their activity history, or helping a patient reach certain goals towards their overall well-being. Comprehensive movement history can be combined with device usage patterns, eating habit data, self-reported well-being data, and other relevant sources to establish a more holistic perspective of a patient’s health. Giving users and healthcare workers access to and insights on the data that they generate every day can promote healthier habits, increase physician efficacy, and promote overall well-being. The author proposes the idea of a centralized system for user data tracking. This could support cross-platform devices, and tie into other fitness and well-being apps to provide a centralized and holistic view of a user’s health. A system of this nature could also tie in information from patient portals, including test results, checkup info, and prescription information.

7. Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Gregor von Laszewski for his invaluable feedback on this paper, and Dr. Geoffrey Fox for sharing his expertise in Big Data applications throughout this course.

8. References

-

Yetisen, Ali K. (2018, August 16). I Retrieved November 15, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6541866/ ↩︎

-

Piwek L, Ellis DA, Andrews S, Joinson A. The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers (2016, February 02). I Retrieved November 11, 2020 from https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1001953 ↩︎

-

Loncar-Turukalo, Tatjana. Literature on Wearable Technology for Connected Health: Scoping Review of Research Trends, Advances, and Barriers (2019, September 21). I Retrieved December 1st from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6818529/ ↩︎

-

Glasgow, Russell E. Realizing the full potential of precision health: The need to include patient-reported health behavior, mental health, social determinants, and patient preferences data (2018, September 13). I Retrieved November 15, 2020 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6202010/ ↩︎

-

Malekzadeh, Mohammad. Mobile Sensor Data Anonymization (2018). I Retrieved September 18, 2020 from http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3302505.3310068 ↩︎